Several of my articles have focused on claims made by paranormal TV celebrity Zak Bagans. Between his still-popular TV show and his Las Vegas museum of “haunted” items, he tends to insert himself into the spotlight by promoting extraordinary claims that don’t always turn out to be accurate, factual, or honest. Due to a plethora of source material he provides, I have a Google alert set for his name, and I follow his museum on Twitter. It was the latter that kicked off this article.

In a Twitter post from January 14, 2019, Bagans posted “Just received in the mail one of the MOST INCREDIBLE artifacts I was happy to win at auction for @Haunted Museum. The Titanic Captain’s ‘Haunted Mirror’ complete with 1922 stamped letter of authenticity that states Captain’s housekeeper saw his ghost in mirror after the wreck.” Honestly, Bagans really doesn’t need to another “haunted mirror” in his museum (see my article “A Closer Look at the Bela Lugosi ’Haunted’ Mirror”), but this new acquisition is really no surprise.

Another Twitter post referencing the new mirror is what really got me interested in researching the matter further. In her post, Kelly Wynne wrote “A super exciting, new haunted item from the Titanic will be added to @Zak_Bagans’s Haunted Museum. Read about it here.” The link led to an article from Newsweek, which Wynne wrote, with a headline declaring “Ghost Adventures host Zak Bagans adds Titanic artifact to haunted museum collection” (Wynn 2019). Both the post and headline state that this item is an artifact from the Titanic. As the reader looks over the first sentence of the article, we see the claim has been slightly altered: “Ghost Adventures star Zak Bagans has acquired another odd artifact, this time, withties to the Titanic” (emphasis mine). So which is it? Was it salvaged from the Titanic, or does it have some vague or tenuous ties to the Titanic? Maybe it was owned by one of the thousands of people who were on the Titanic? Who knows?

Whatever the case, the story still piqued my interest, so I fired up Google. It didn’t take long to find information on the mirror, which after all the repeating, ended up not being much. According to website Antique Collecting, “The silver-framed easel mirror sat on Captain Edward John Smith’s dressing table at his home in Stoke-on-Trent.” This account, with various others, shows the mirror was a personal possession of Captain Smith that remained in his home. It is not from the Titanic, nor is it a “Titanic artifact.”

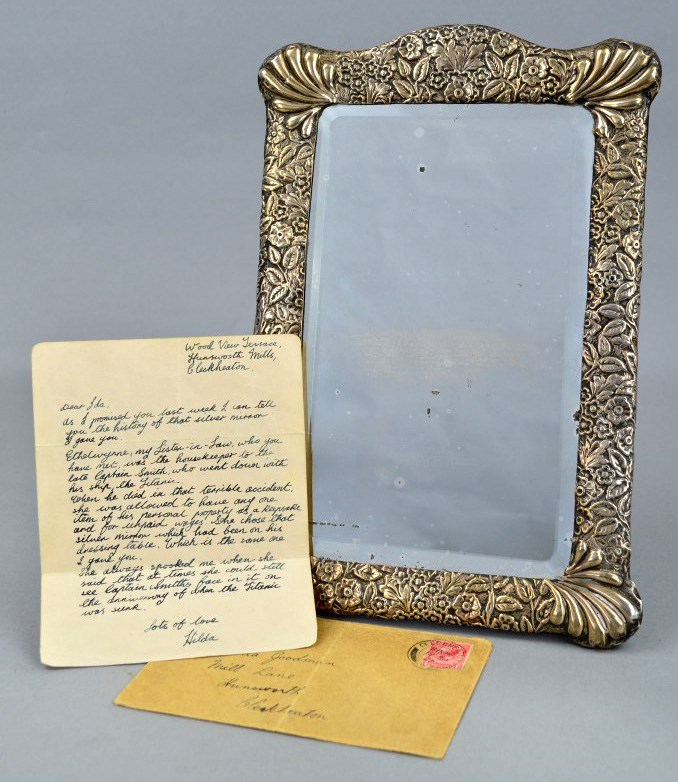

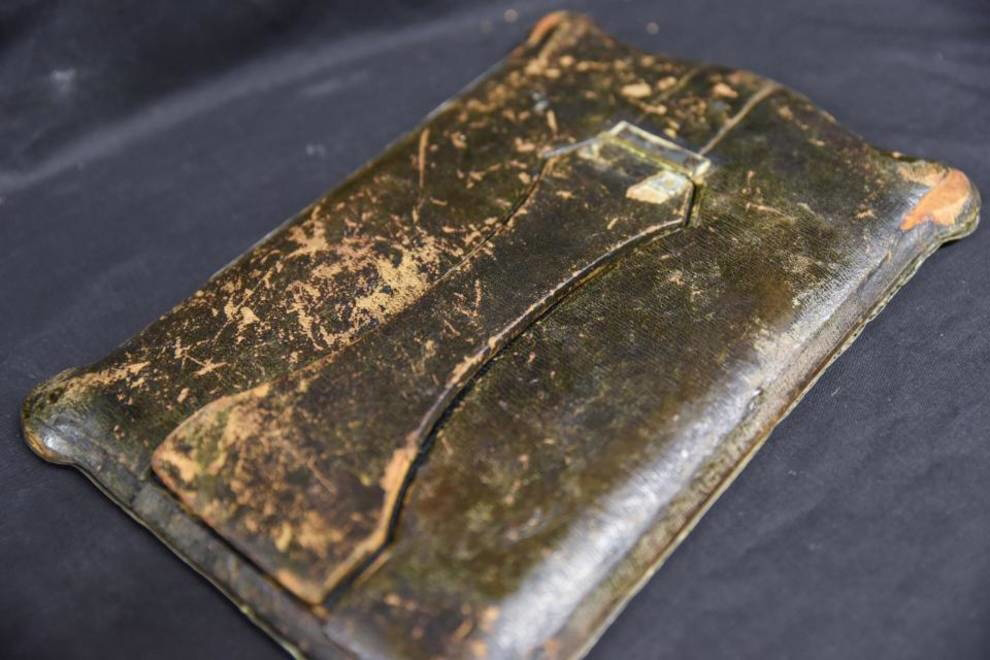

The mirror itself has a silver frame engraved with a floral design. The backing and easel look to be a well-worn, leather-type material. When compared to an iPad, the frame is estimated to be about twelve inches in height. There’s an additional item that comes with the mirror: “Included with the mirror is a small brown envelope containing a handwritten note explaining the item’s provenance” (Antique Collecting 2018). This letter seems to be the sole source of historical background of the mirror, as no other documentation has been presented or made available to the public.

There is a lot to unpack in that short quote. The statement that the letter is “explaining the item’s provenance” really stuck out to me. The statement is also repeated across multiple websites that have reported on the story. Provenance is defined as “the history of ownership of a valued object or work of art or literature” by the Merriam-Webster dictionary. Establishing provenance can take many forms, and the website Lofty.com warns us that “Verbal history can be interesting, but there should also be old photographs of the item in the family collection, bills of sale, and other documentation that can prove the statements are true. Memory, including family lore, is not always accurate and tends to inflate over time” (Lofty 2018). Other types of provenance include previous appraisals, a signed certificate of authenticity from a widely respected and recognized authority (Bamberger 2017), names of previous owners that can be identified and verified, and so on.

The only documentation offered as provenance, before or after the auction, is the 1922 envelope and letter. I decided to take took a closer look at these important items, since it seems to be the sole evidence supporting the mirror belonging to the Titanic captain—again, not from the Titanic—and of course, that it is haunted. Most outlets sharing this story simply copy and paste (as I’m about to do) the following: “After his death, Captain Smith’s housekeeper Ethelwynne was invited to choose any one item of his property as a keepsake and in lieu of wages. The letter, which was penned by Ethelwynne’s sister-in-law Hilda, says that the housekeeper chose the silver mirror. The note—addressed to someone called Ida—then chillingly adds: ‘She [Ethelwynne] always spooked me when she said that at times she could still see Captain Smith’s face in it on the anniversary of when the Titanic was sunk’” (Archer 2018).

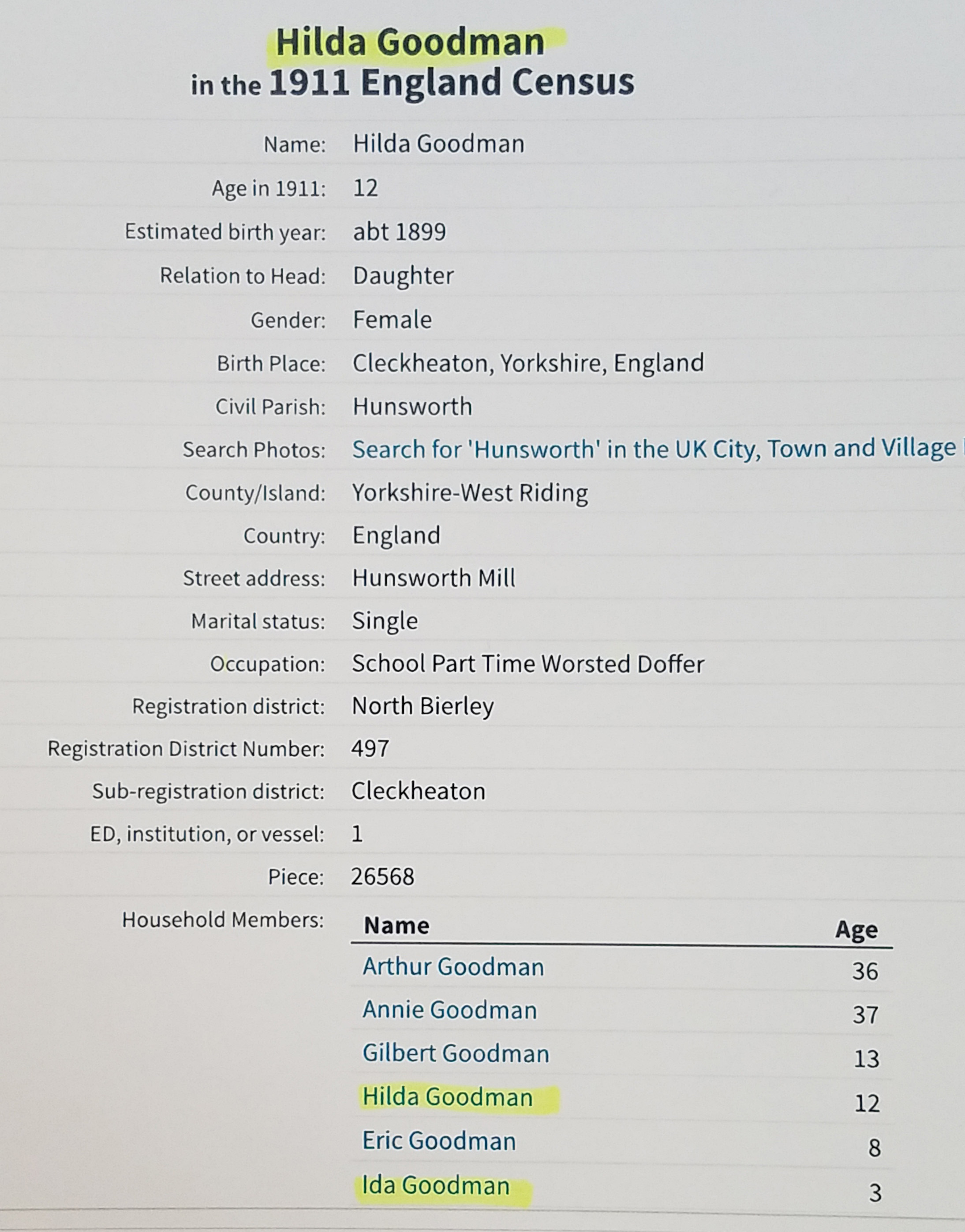

The “someone called Ida” is Ida Goodman, as is made quite clear on the envelope. Ida lived on Mill Lane, Hunsworth, Cleckheaton. This is indeed a real place, located in the borough of Kirklees, West Yorkshire, England. Hilda, the author of the letter, listed her address in the top right corner of the letter: Wood View Terrace, Hunsworth Mills, also in Cleckheaton. With a bit of digging, courtesy of Ancestry.com, I was able to identify both women: Ida Goodman and—drumroll, please—Hilda Goodman. They are, in fact, sisters (Hilda is the older sister). They grew up in Cleckheaton, along with brothers, Gilbert and Eric.

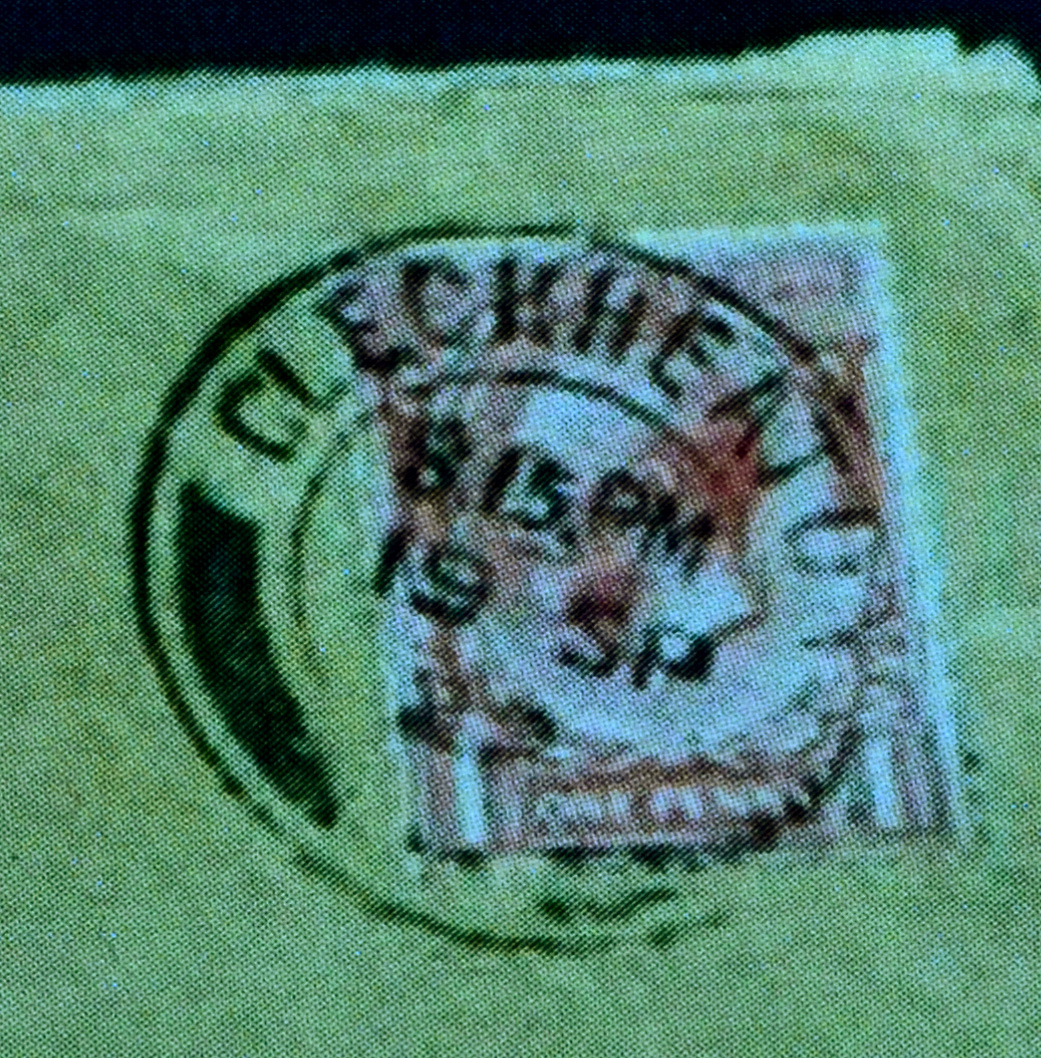

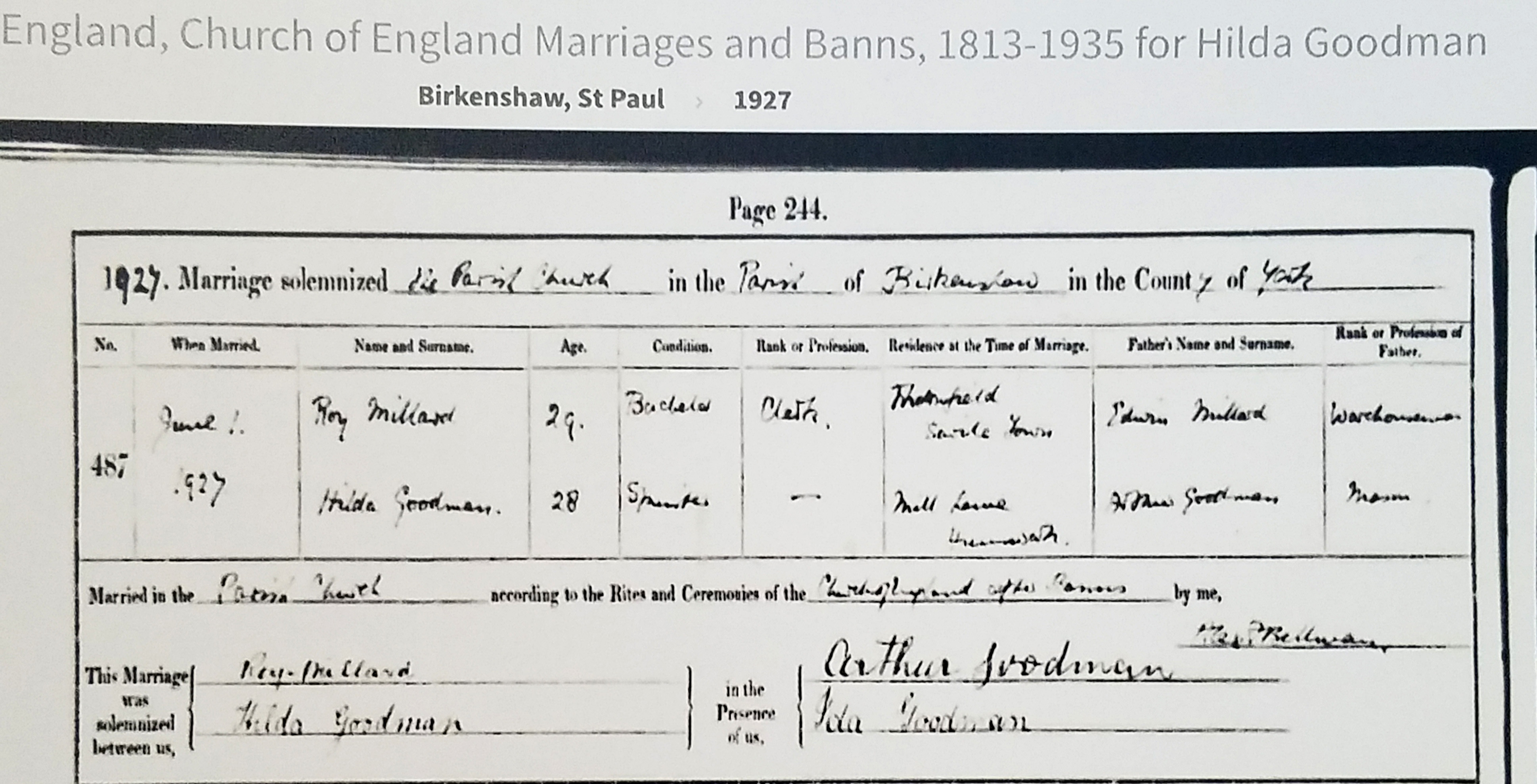

In the letter, written by Hilda, she refers to the housekeeper, Ethelwynne, as “my Sister-in-Law”—this indicates that Ethelwynne is from her husband’s side of the family. This brings up two issues; first, this indicates Hilda was married. The issue is that she was not married in 1922. On page 244 of the West Yorkshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns 1813–1935, it shows that Hilda Goodman married Roy Millard on June 1, 1927, at the age of 28. Her residence at the time of marriage is listed as Mill Lane, Hunsworth (the family home). This contradicts the date of 1922, believed to be stamped on the envelope, since Hilda didn’t marry until five years later. However, after a closer examination of images provided, I believe the stamp does say 1927, and not 1922 as has been promoted. I believe this to be a mistake that has been repeated wherever the story was reported.

The second issue is Ethelwynne, the alleged housekeeper of Captain John Edward Smith. I began researching the genealogy of Hilda Goodman, since Ethelwynne is supposed to be her sister-in-law. As stated above, Hilda married Roy Millard in 1927. Millard had an older brother, Harold, and younger sister, Carrie—but no Ethelwynne. I took a deeper dive into the family tree; Harold married Alice Maud Stott (who had no sisters), and Carrie married John K. Oxley (who had three sisters: Lillian, Eliya, and Minnie)—still no Ethelwynne to be found. No matter how far I went, I could not find anyone named Ethelwynne related to Hilda, the author of the important letter.

I began searching England Census records for 1911, which was the closest available to 1912 when Captain Smith died with the sinking of the Titanic. I was still looking for a woman named Ethelwynne, and although many came up, none showed any relationship with Hilda Goodman or her extended family. I finally pulled the 1911 England Census for Edward John Smith. There are seven people registered: Edward John Smith (head), Sarah Eleanor Smith (wife), Helen Melville Smith (daughter), Thomas Martin (medical student/visitor), Florence Mary Cury (visitor), Ann Brett (housemaid domestic), and Mabel Lucy Sukper (cook domestic). Of course, the servants could have certainly changed by the following year or perhaps there were servants not living in the house. However, this is the only record we have that names a housemaid: Ann Brett (age 27).

Ann Brett is listed as single (unmarried) in 1911. She is also listed as single in the 1939 England and Wales Register, working as a domestic servant for John and Ellen Rowlands. Going back a bit, the 1891 England Census lists Brett having three sisters and one brother, none of which are named Ethelwynne. The “letter of authenticity” (Bagans 2019), which was promoted on the Richard Winterton Auctioneers LTD website as “a handwritten note explaining the item’s provenance” (Richard 2018), doesn’t seem to be doing its job.

When we get down to it, the letter does very little to establish the ownership of the mirror. Although it describes a silver mirror, it doesn’t include other materials (such as the backing), the floral pattern, or the dimensions of the mirror. This opens up the letter to describing any silver mirror. Hilda also doesn’t describe how she came into possession of the mirror, only that she gave it to her sister, Ida. By 1939, Ida is listed as incapacitated and living with her older sister, Hilda, and her husband, Roy.

In addition, there is no receipt provided (for the unpaid wages due Ethelwynne) or any photographs that would establish that this mirror was in Captain Smith’s residence (on his dresser) or with anyone mentioned in the letter (Ida, Hilda, or Ethelwynne). I was hoping to find some connection back to Captain Smith, but I kept hitting dead ends.

The mirror listing on the Richard Winterton Auctioneers LTD website, richardwinterton.co.uk, clearly states “Included with the silver-framed easel mirror … is a handwritten note explaining the item’s provenance … .” So, I reached out to them via email. I explained that I had done a bit of research, had run into some discrepancies, and asked if there was any additional documentation with the mirror besides the letter that would fill in the gaps of my research. I received a reply from Alex Keller, head of Media and Relations, who stated “The item you mention sold in December and was shipped shortly after. The lot contained numerous related paperwork but unfortunately, I can’t go into any further detail as of course we don’t have it any longer. We’d be very interested to hear how your ongoing research progresses.”

I was rather disappointed they didn’t have any records related to the sale. I also found it odd that they were interested in my research, offering none of their own. It seemed they made no effort to verify the provenance of the mirror—at least none that they made public. To be fair, Keller did mention “numerous related paperwork,” so perhaps there is something more to this story. However, as of this moment we have no idea what that additional paperwork might be. Furthermore, in every listing I came across, there was nothing else presented in support of the mirror belonging to Captain Smith—just the letter.

Another part of the story, as reported by sites such as StoryTrender.com and SingularFortean.com, state “Descendants (or relatives) of Ethelwynne kept it in their possession for generations until it was discovered in a deceased estate in Wolverhampton, England; after which it came into the possession of current owner David Smith, who has held the mirror for the past five years.” This brings up more questions: Who are these relatives/descendants? Is there an actual record of which relatives owned it, aside from Ida and Hilda—who have been found not to be related to the mysterious Ethelwynne. Also, we are told it was “discovered” at an estate. Whose estate? Did the letter from Hilda follow the mirror the entire time—eighty-six years—until it was “discovered” and came to David Smith five years ago? Where did David Smith acquire it? The story doesn’t actually state he was the one that discovered it at the estate sale. These are details that should have been included as documentation of provenance.

At this point, I didn’t know what to think about the letter. Was it genuine? Was it a forgery? Was there something in it—a clue—that I was missing? I’m not an expert in document authentication, but I do know someone that is. I called Joe Nickell, senior research fellow of the Committee for Skeptical Inquiry. He also has an extensive background in forensic document examination (and authentication). After doing a little research of his own, he called me back to tell me what he thought. He didn’t see anything particularly out-of-place on the surface but brought up the fact that we’re not looking at the actual document but instead just a photo of it. Without the original document, there’s little examination to be done.

Another point Nickell brought up was that unless there were other verified writing samples from Hilda (Goodman), there was no way to verify if the letter was actually written by her hand. Although Nickell saw nothing in the writing to suspect a forgery, he did mention that it was possible that anyone could have written the short letter in its entirety; that a forger could have written the letter themselves and simply used an old envelope. The letter and envelope simply can’t be taken as authentication of anything on their own. To be clear, I’m not saying the letter is forged, but merely that it can’t be ruled out.

And then there is the ghostly component to this story, in which the auction house definitely used to boost interest. In the letter, Hilda writes “She always spooked me when she said that at times she could still see Captain Smith’s face in it on the anniversary of when the Titanic was sunk.” This paragraph that ends the letter has been used to promote the mirror as haunted, spawning headlines such as “Titanic Captain’s ‘haunted’ mirror could sell for £10,000” (Lindley 2018) and “Haunted mirror ‘possessed by the ghost of the Titanic captain’ up for auction” (Coles 2018). This marketing tactic no doubt is what caught the attention of Zak Bagans (and it worked).

In the Twitter post by Zak Bagans, he wrote “The Titanic Captain’s ‘Haunted’ Mirror; complete with 1922 stamped letter of authenticity that states Captain’s housekeeper saw his ghost in mirror after the wreck.” In fact the letter does not specifically say anyone saw a ghost or any kind of spirit manifestation at all. The description brings to mind someone reminiscing about someone they knew. Ethelwynne, if she actually existed, did not describe witnessing a ghost; she was remembering someone that was dear to her on the anniversary of their death. The mirror was a keepsake, a small item kept in memory of the person who originally owned it. Who hasn’t picked up an item once owned by a friend or relative, maybe even an old coworker, and thought of them or “saw their face”? I own a softball jersey from a former coworker and good friend who unfortunately died several years ago in a tragic accident. Occasionally when I look up on the wall (where it hangs in a shadow box), I can still see his face and even hear his voice trading Star Wars quotes with me. I’m not experiencing a ghost, nor is the softball jersey haunted. I’m reminiscing happy memories of a friend I miss; nothing more.

I’m left wondering if this mirror was ever owned by Captain Smith. The letter, from which practically all of the information reported about the mirror originates (and is often embellished), has been shown to be flawed or at least incomplete and unvalidated; Ida and Hilda, found to be sisters, have no connection with a woman named Ethelwynne. Census records the year before Captain Smith died shows the housemaid was named Ann Brett, who also has no connection to Ethelwynne, Ida, or Hilda. Putting it in perspective, the provenance appears to be based off a second-hand story originating from a letter we’re not sure was even written by the person whose name appears at the bottom of it. Granted, there could be other paperwork that fills in the gaping holes in the history of the mirror, as hinted at by Alex Keller, that could verify everything claimed about the mirror (besides the ghost). In that case, I’ll certainly update this article to reflect that new information. However, no such paperwork has ever been referenced in the news coverage, including the videos in which Richard Winterton (of the action house) appears in with the mirror.

This project was a great exercise in researching the provenance of an item from an auction, something I haven’t done before. Claims were made, and although I started out trying to verify them (I really wanted to connect the dots), they ultimately fell short by the information made available. Granted, I most likely put a lot more work into this than was necessary, but it was a fun and enlightening adventure in which I learned more about auction items, forensic document analyzation, and honed my genealogy skills a little more. The mirror was expected to fetch over £10,000/almost $13,000 at the December 12, 2018, auction (richardwinterton.co.uk 2018), but ended up selling well below that amount; £2,800/$4,500. Nevertheless, I have no doubt the mirror’s past and ghostly antics will grow by leaps and bounds once it becomes part of the Not-So-Haunted Museum—as was announced on February 1, 2019.

I’ll end this column with some good advice for future auction bidders via Alan Bamberger from the website ArtBusiness.com: “Before bidding on or buying any art, your job is to make sure any such provenance offered by sellers is correct, legitimate, verifiable and does in fact attest to the authorship of the art” (Bamberger 2017).

*Special appreciation to Joe Nickell for his help, advice, and sharing his extensive knowledge with me.

References

- Antique Collecting. 2018. Available at https://antique-collecting.co.uk/2018/10/30/titanic-captains-mirror-in-staffordshire-sale/.

- Archer, Megan. 2018. Titanic captain’s haunted mirror could fetch £10,000 at Staffordshire auction. Available at https://www.expressandstar.com/news/local-hubs/staffordshire/2018/11/08/titanic-captains-haunted-mirror-could-fetch-10000-at-staffordshire-auction/.

- Bagans, Zak. 2019. Twitter post.

- Bamberger, Alan. 2017. Art Provenance: What It Is and How to Verify It. Available at https://www.artbusiness.com/provwarn.html.

- Coles, Dan. 2018. Haunted mirror ‘possessed by the ghost of the Titanic captain’ up for auction. Available at https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/weird-news/haunted-mirror-possessed-ghost-titanic-13608741.

- Gentile, Ashlyn. 2017. How To Prepare A Certificate of Authenticity. Available at https://www.agora-gallery.com/advice/blog/2017/12/02/prepare-certificate-authenticity/.

- Lindley, Simon. 2018. Titanic Captain’s ‘haunted’ mirror could sell for £10,000. Available at https://news.justcollecting.com/titanic-captain-haunted-mirror-auction-10000/.

- Lofty. 2018. What Is Provenance and Why Is It Important? Available at https://www.lofty.com/pages/what-is-provenance-and-why-is-it-important.

- Merriam-Webster. 2019. Provenance. Available at https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/provenance.

- Richard Winterton Auctioneers. 2018. December Fine & Decorative Arts Sale. Available at https://www.richardwinterton.co.uk/latestnews/1416/December+Fine+&+Decorative+Arts+Sale.htm.

- Winterton, Richard. 2018. Twitter post. Available at https://twitter.com/Auctionwint/status/1072830197676810240.

- Wynne, Kelly. 2019. ‘Ghost Adventures’ Host Zak Bagans Adds Titanic Artifact To Haunted Collection. Available at https://www.newsweek.com/ghost-adventures-host-zak-bagans-adds-titanic-artifact-haunted-collection-1293826.