In the days after the mass shooting in San Bernardino, a dear friend and single mother made an impassioned plea on her Facebook page. After seeing many calls for increased gun control, she explained that she had been a victim of assault in the past and would not be giving up her handgun anytime soon. She said maintaining her permit was difficult to do—“as it should be”—but she was clearly upset about the many calls for additional controls.

While I sympathize with my friend’s desire for security, she has fallen for one of the most common and most dangerous misconceptions Americans hold. According to a 2013 Gallup poll, the top reason U.S. gun owners keep a firearm is “personal safety/protection.” Fully 60 percent of gun owners gave this reason, and the next most common reason was “hunting” at 36 percent.

Sadly, buying a gun does not make you safer. To the contrary, the evidence suggests that bringing a gun into your home increases the chances you will be killed. You are to be forgiven if you have not heard more about this. There is an extremely profitable industry based on the myth that guns are an effective means of self-protection, and it would be bad for business if this information were more widely known. Furthermore, the myth that weapons make you safer has benefited from a deliberate campaign against science and the collection of gun violence data.

The Campaign Against Gun Violence Research

In 1993, Arthur Kellerman and colleagues published a landmark study in the New England Journal of Medicine entitled, “Gun Ownership as a Risk Factor for Homicide in the Home.” The Kellerman study examined 388 cases of homicide that occurred in the home or within the property borders of the home and an equal number of matched control households. The data were drawn from the most populous counties in three different states (Ohio, Tennessee, and Washington). Kellerman famously found that “keeping a gun in the home is independently associated with an increase in the risk of homicide in the home.” Indeed, controlling for other factors, households where a gun was present were 2.7 times more likely to experience a homicide and 77 percent of the victims were killed by someone they knew: a spouse, partner, relative, friend, roommate, or acquaintance.

Kellerman and colleagues concluded:

Despite the widely held belief that guns are effective for protection, our results suggest that they actually pose a substantial threat to members of the household. People who keep guns in their homes appear to be at greater risk of homicide in the home than people who do not. Most of this risk is due to a substantially greater risk of homicide at the hands of a family member or intimate acquaintance. We did not find evidence of a protective effect of keeping a gun in the home, even in the small subgroup of cases that involved forced entry. (p. 1090)

The Kellerman study caused quite a stir, and pro-gun advocates were quick to try to criticize it. But the gun lobby was not satisfied with merely trying to debunk the study. The National Rifle Association (NRA) acted to prevent research on gun violence altogether.

The Kellerman study employed telephone and face-to-face interviews, making it very expensive to conduct, and the investigators had received funding from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention’s National Center for Injury Prevention (NCIP). The NRA response was to advocate for the complete elimination of the NCIP. They failed at that effort, but they were able to effectively block all federal funding of research on gun violence. In what has come to be called the Dickey Amendment—after its author, former U.S. Representative Jay Dickey (R-AR)—Congress placed language in the 1996 omnibus funding bill that prohibited any funds given to the CDC from being used to “advocate or promote gun control.” In addition, Congress cut the CDC’s budget by $2.6 million, the same amount that had been allocated for firearm injury research in the previous year. The effect of the amendment was chilling and all federal funding for firearm injury research quickly disappeared, a condition that is still in effect today.

Former Representative Dickey has subsequently changed his position and is now in favor of the CDC funding gun violence research. But last summer Congress quietly renewed the ban on firearms research, voting down an amendment that would have lifted the ban. When asked why the CDC amendment was not supported, Speaker of the House John Boehner replied, “Because guns are not a disease.”

As I write this, Congress is again in the process of passing an omnibus spending bill. Despite the efforts of Democrats to eliminate the Dickey amendment, it survives. The NRA-backed ban on gun violence research remains in effect.

What Does the Available Research Show?

Although federal funding has been cut off for almost two decades, investigators have found other ways to conduct research, and there are some consistent findings.

1. Access to Firearms Increases the Risk of Being a Victim of Homicide.

The primary result of the Kellerman study has held up over time. In 2014, researchers from the University of California at San Francisco published a meta-analysis summarizing all the available controlled studies in the Annals of Internal Medicine. They found the odds of being a victim of homicide were between 1.6 and 3.0 times higher when the victim had access to a firearm. The wide availability of firearms is only one of the factors contributing to the high rate of homicide in the United States, but, contrary to popular belief, you are safer if you don’t have a gun at home than if you do.

2. Women Are Especially at Risk of Homicide When a Firearm is Present.

The same 2014 meta-analysis found that the increased risk of homicide victimization created by access to a firearm was significantly greater for women than for men.

3. Access to Firearms Greatly Increases the Risk of Suicide.

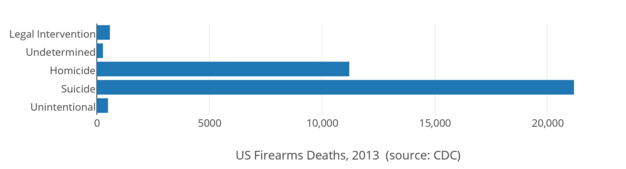

Although it gets far less attention, suicide is a much bigger problem than homicide. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, in 2013 there were 2.5 times as many suicides as homicides in the United States, and many of them were committed using a firearm. Of all firearm deaths, 63 percent were suicides and only 33 percent were homicides. Furthermore, 51 percent of all suicides were committed with a firearm.

Many suicides are impulsive acts that can often be prevented if there is time. Unfortunately, firearms are quick and highly lethal. Ready access to a gun makes it possible to act on impulse with tragically irreversible results. The 2014 meta-analysis also looked at controlled studies of suicide risk and found that access to a firearm increased the odds of suicide by ratio of 3.24-to-1.

4. Firearms Are Not Very Effective at Deterring Crime.

One of the most popular arguments in favor of firearm ownership is that guns are useful for self-defense in criminal encounters. A frequently cited 1995 study by Gary Kleck and Marc Gertz estimated that Americans used guns for self-defense approximately 2.5 million times per year. This figure has been widely criticized, and more recent studies using superior methodologies have painted a very different picture.

For example, in April of 2015 a study published in Preventive Medicine by David Hemenway of the Harvard School of Public Health and Sara J. Solnick of the University of Vermont examined data from the National Crime Victimization Surveys for the years 2007 through 2011. Hemenway and Solnick found that out of 14,000 episodes in which the victim came into contact with the offender (robberies, burglaries, assaults, etc.), the victim used a gun to threaten or attack the perpetrator in only 127 cases (0.9 percent). Hemenway and Solnick also found that men and women were equally likely to be the victims of contact crimes, but men were three times more likely to use a gun in self-defense. In over 300 cases of sexual assault there was not a single incident of self-defense gun use.

For those who used a gun in self-defense, the chances of being injured in the incident (10.9 percent) were essentially equal to those who took no action at all (11.0 percent). There was some evidence that the use of a firearm resulted in less loss of property, but guns were no more effective than other methods of self-defense in this regard.

Dr. Hemenway summarized the findings this way:

The National Crime Victimization Surveys, the gold standard for crime estimates, indicates that using a gun in self-defense is quite rare (less than 1% of contact crime) and that it does not appear to be more effective than many other measures of self-defense or protection in reducing the likelihood of being injured. Not having a gun does not render potential victims of crime either helpless or easy marks.

A Dangerous Myth

In 2012, the U.S. gun industry was estimated to be worth $31.8 billion per year. If the recent Gallup poll is an accurate measure of why people purchase guns, a large part of the industry’s profits are based on the false belief that owning a gun makes you safer—that a pistol in the drawer will protect you from all the bad guys out in the dark. This is not the first or only industry to profit by spreading false beliefs, but it is hard to imagine one where the public health costs are as high.

In fact, gun owners would be less likely to be victims of homicide and especially suicide if they got rid of their guns. In addition, taking no action during a criminal encounter would make them no more likely to be injured than if they used a gun.

It is easy to understand the emotional appeal. I am quite certain my gun-owning friend feels safer. Psychological research is replete with examples of how emotion and intuition can lead us astray. When asked what one thing he would eliminate if he had a magic wand, Nobel Prize winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman said “overconfidence.” The kind of overconfidence that makes governments think wars will be easily won and makes investors believe that housing prices will always go up.

Many gun owners undoubtedly suffer from overconfidence, too. Thanks to a well-funded advertising campaign, they have a particular image of how a gun would affect any future conflicts in their homes. They have been told, “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” But of course, real life is not a melodrama with easily identifiable good guys and bad guys. Most of the perpetrators of violence are not strangers coming in from the darkness.

It is likely that many gun owners also discount the possibility that they or someone in their home will become suicidal in the future and, as a result, don’t consider the implications of having a gun in the drawer when that happens.

It is easy to say, “That would never happen to me.” Many gun owners undoubtedly believe they can beat the odds because they are careful and wise, but the evidence is clear. If you care about your safety and the safety of your loved ones, get rid of your guns.