Ignorant of your own ignorance. Frequently applied in a political context, the Dunning-Kruger (DK) effect has rapidly become a famous psychological concept. It describes a kind of double-whammy. If you suffer from the DK effect, you know very little about a subject—which is bad enough—but you also have the false impression that you know considerably more than you do. In a world where the views of experts are regularly dismissed (Nichols 2017) and many internet users think they know more about medicine and foreign policy than people who actually studied those subjects in school, the DK effect seems to explain a lot. People who are unskilled or unschooled in a subject also suffer from a “metacognitive deficit.” Metacognition is thinking about your own thought processes, and it is separate from the basic thinking you do while solving a problem or taking a test. According to Dunning and Kruger, people who are ill informed often don’t know it.

But not long after the DK effect was identified, it was challenged. This is only proper and part of the usual scientific enterprise, but in this case, some authors came to the conclusion that what Dunning and Kruger had seen was just a statistical artifact of the process of measuring people’s performance and expectations. The objections to the DK effect can get quite technical, but I will do my best to keep it simple.

The Basic Effect

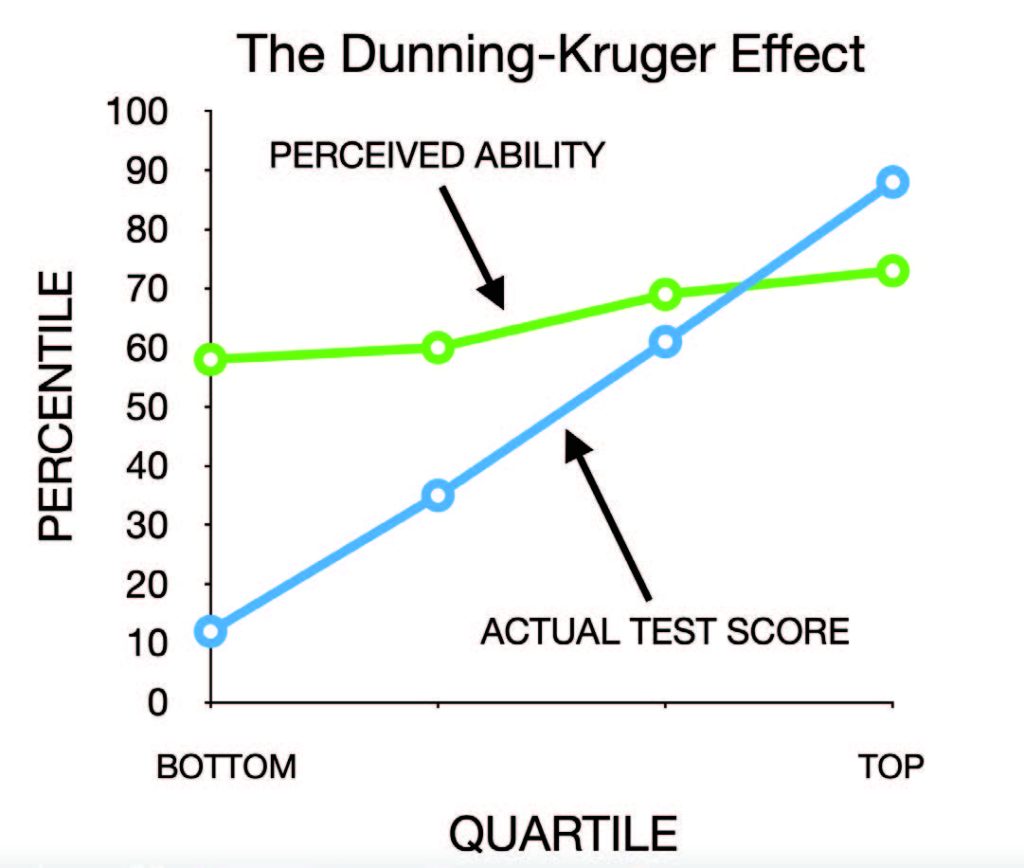

In Study 2 of Kruger and Dunning’s original article (Kruger and Dunning 1999), the authors gave college students a twenty-item test of logical reasoning with questions drawn from the Law School Admissions Test. After completing the test, each student was asked to rate their performance relative to others on a percentile scale and also to predict the number of items they got correct. In presenting the results, Kruger and Dunning grouped the participants into quartiles (e.g., lowest 25 percent of scorers, next 25 percent of scorers, etc.). The classic finding is shown in Figure 1, a hypothetical graph that I created on my computer. People who scored low relative to other people greatly overestimated how well they did. Conversely, the people who scored in the top quartile slightly underestimated their performance. This kind of finding has been replicated many times by researchers in different laboratories with tests on a variety of subjects.

Maybe It’s Just Noise

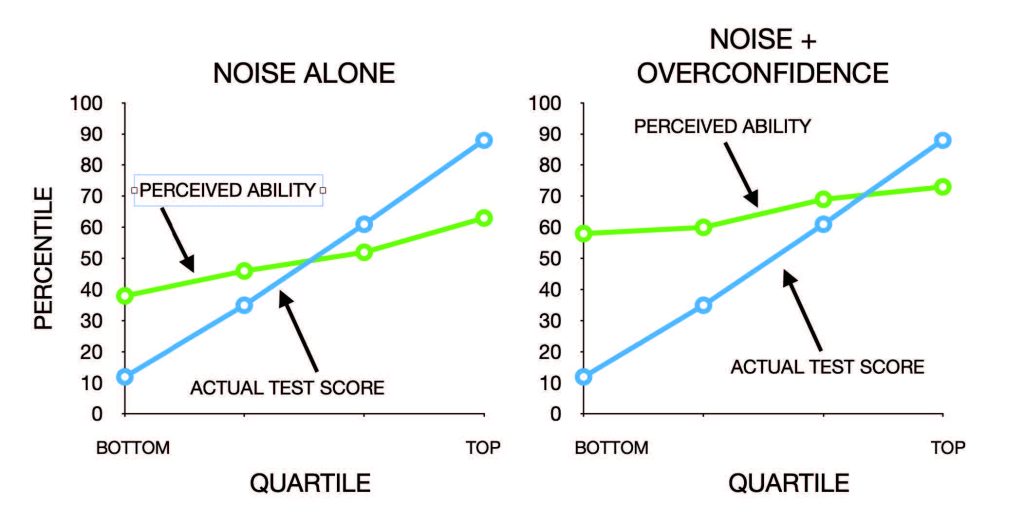

One of the first challenges to the DK effect was that it was just noise, random errors of measurement. This was a quite reasonable hypothesis because random error added to the blue actual score diagonal of Figure 1 would tend to flatten the line. At the extremes, random error will bump up against the 0 and 100 endpoints of the scale, causing the quartile averages to move toward the center (see the left panel of Figure 2). Meanwhile, scores in the center two quartiles are farther from the endpoints and, assuming random errors both above and below the accurate score, we would expect those means to move less. The result is a kind of regression to the mean: the tendency of extreme scores to be followed by scores that are closer to average. Several researchers have run simulations that produced this effect by introducing random error to the participants’ estimates of their performance (Burson et al. 2006; Jarry 2020; Vincent 2020).

But adding noise only gets you part of the way to the classic DK effect. As you can see, in the classic graph (Figure 1), the separation is greatest for the low scorers, and the crossover to underestimating performance happens between the two highest quartiles. The second step that gets you the rest of the way to the DK effect is to add in some overconfidence. It goes by several names, including the “better than average effect” or the “Lake Wobegon effect,” but it describes a widespread tendency to overestimate one’s ability. In a classic study, 60 percent of a sample of U.S. drivers said they were in the top 20 percentile of drivers on the dimension of safety—a mathematical impossibility (Svenson 1981). Similarly, another study found that 42 percent of respondents said they had more friends than their friends had, and only 16 percent said they had fewer friends than their friends had. In fact, due to a mathematical oddity called the “friendship paradox,” most of us have fewer friends than the average number of friends our friends have (Zuckerman and Jost 2001).

Adding an optimistic bias to the participants in a DK simulation has the effect of lifting the perceived performance line up for everyone, and “voila!” you get the picture in the right-hand panel of Figure 2. This looks very much like the classic DK effect as seen in Figure 1, and these combined factors have been simulated by several researchers to produce the classic DK pattern (e.g., Vincent 2020).

The psychological implications of this explanation are quite different from what Dunning and Kruger have suggested. It would still be true that the low scorers are substantially off in their assessment of their own abilities, but if the observed separation at the bottom of the scale is produced by noise plus overconfidence, then there is nothing special happening for low scorers—other than, of course, they don’t know much about the subject being tested. Dunning and Kruger have described low scorers as having a metacognitive deficit—or “meta-ignorance” as Dunning (2011) has referred to it—that is not shared by the people who score better. The noise plus overconfidence combination suggests that people differ in just one way: their knowledge of the subject area.

Sorting It Out

Last year as I was finishing up my latest book (Vyse 2022), a reader pointed out that I had mentioned the DK effect and that it was the reader’s impression that the effect had been revealed as a statistical artifact, that it wasn’t real. I’d read some of the criticisms and had formed my own opinion. Admittedly, I loved the notion behind the DK effect—being ignorant of your own ignorance. I was particularly fond of a 2018 (pre-pandemic) study that showed that over a third of participants thought they knew more about the causes of autism than doctors and scientists (Motta et al. 2018). The authors found participants who showed this overconfidence about their medical knowledge were more likely to support the role of nonexperts (e.g., celebrities) in setting mandatory vaccine policies.

Knowing I had a preference for one view, I began to worry I was making a mistake and that the mistake would be memorialized in my book for all time. So, I read as much as I could from the critics, and I contacted David Dunning directly to ask him if he still believed the DK effect is real. He was quite firm in his belief that the effect is real and not merely a statistical fluke. He supported his view by pointing to the many contexts in which it had been replicated—which, while impressive, I did not accept as proof—and to some studies testing alternative explanations for the DK effect. The most convincing of these was a recent large-scale study published in Nature Human Behaviour (Jansen et al. 2021) that included many improvements over previous studies. For example, Jansen and colleagues conducted two studies, one on logical reasoning and one on grammar, each with over 3,000 online participants. This large sample guaranteed that there would be sufficient people at the extremes of high and low performance to accurately trace the relationship between actual and expected test scores.

The results showed an astonishing level of inaccuracy in expected scores. For example, on the grammar test, the lowest performers who got either zero or one question correct (out of twenty questions) expected on average to have scores of approximately twelve correct(!). By comparison, high performers who got all twenty questions correct underestimated their performance by a much more modest amount, expecting on average to get approximately sixteen correct.

The authors created a Bayesian mathematical model that, in simple terms, suggests that people make a rational effort to adjust their estimates of their performance based on experience. For our grammar and logical reasoning test takers, no feedback was given during the test; so, if people adjusted their expectations of their total score, it would have been on the basis of rather murky intuitions about how well they had done. Under these circumstances, a person who comes in expecting to get approximately sixteen out of twenty correct but—unbeknownst to them—gets only four correct will often not have enough information to adequately adjust their estimate downward. They may be acting rationally but with insufficient information. Assuming most people come in with rosy expectations, this rational Bayesian model might explain why low scorers overestimate their performance. Jansen and colleagues (2021) tested this model but found that it did not fit the data as well as a model that took into account the participant’s actual score. This is because low scorers were even farther off in their estimates of their scores than the rational Bayesian model could account for. A news item accompanying the article in Nature Human Behaviour summed up the results up this way:

In other words, not only is the Dunning–Kruger effect not merely a statistical artefact at the group level, it also cannot be explained solely by Bayesian shrinkage in the rational estimations of individual participants. … Jansen and colleagues’ model fits make clear that the data are best captured by a performance-dependent change in estimation noise. (Mazor and Fleming 2021, 677)

In other words, the observed DK effect was not created just by overconfidence plus random noise or by some rational but flawed process employed equally by all participants. Poor performers were different. They were farther off in their predicted scores than middle and higher performers, and when the model took into account their actual performance on the test, it fit the data better.

Of course, models are only as good as their starting assumptions, and the debate will continue. But for now, in my opinion, the balance of evidence seems to be in favor of the reality of the DK effect. Many people who lack knowledge in a subject area suffer doubly: they are both ignorant and ignorant of their ignorance. This is a troubling idea. But perhaps the hardest lesson to learn about the DK effect—often stressed by David Dunning himself—is that this problem is not limited to some other group of people safely off in the distance. Depending on the area of expertise, the Dunning-Kruger effect applies to us all. If ignorant enough, under many circumstances, we will fail to recognize how ignorant we are. Ideally, the message of the DK effect is both troubling and humbling.

References

Burson, Katherine A., Richard P. Larrick, and Joshua Klayman. 2006. Skilled or unskilled, but still unaware of it: How perceptions of difficulty drive miscalibration in relative comparisons. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90(1): 60–77.

Dunning, David. 2011. The Dunning-Kruger effect. On being ignorant of one’s own ignorance. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 1st ed., 44: 247–96.

Jansen, Rachel A., Anna N. Rafferty, and Thomas L. Griffiths. 2021. A rational model of the Dunning–Kruger effect supports insensitivity to evidence in low performers. Nature Human Behaviour 5(6): 756–63. Online at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01057-0.

Jarry, Jonathan. 2020. The Dunning-Kruger effect is probably not real. Office for Science and Society. Online at https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/critical-thinking/dunning-kruger-effect-probably-not-real.

Kruger, Justin, and David Dunning. 1999. Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77(6): 1121–34.

Mazor, Matan, and Stephen M. Fleming. 2021. The Dunning-Kruger effect revisited. Nature Human Behaviour 5(6): 677–78.

Motta, Matthew, Timothy Callaghan, and Steven Sylvester. 2018. Knowing less but presuming more: Dunning-Kruger effects and the endorsement of anti-vaccine policy attitudes. Social Science and Medicine 211: 274–81.

Nichols, Tom. 2017. The Death of Expertise: The Campaign against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters. New York: Oxford University Press.

Svenson, Ola. 1981. Are we all less risky and more skillful than our fellow drivers? Acta Psychologica 47(2): 143–48.

Vincent, Benjamin. 2020. The Dunning-Kruger effect probably is real. Medium (December 29). Online at https://drbenvincent.medium.com/the-dunning-kruger-effect-probably-is-real-9c778ffd9d1b.

Vyse, Stuart. 2022. The Uses of Delusion: Why It’s Not Always Rational to Be Rational. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zuckerman, Ezra W., and John T. Jost. 2001. What makes you think you’re so popular? Self-evaluation maintenance and the subjective side of the ‘friendship paradox.’ Social Psychology Quarterly 64(3): 207–23.